R: Who are you and how do you take up space (in Detroit, the world, etc)?

L: I think of myself as an artist these days. I take up space as a Black woman who's interested in unsettling the ways that oppression and anti-Blackness shows up in the world. In the past, that's meant doing work that shapes policy, or doing research that helps us better understand certain phenomena. At the moment, I'm doing similar things but with creative techniques as a tool for asking the same kinds of questions

R: Do you see your practice as a method of organizing? Why or why not?

L: Yes, with a caveat. For example, with Making Room for Abolition as a body of work, the premise there grew out of being frustrated with the urgency and immediacy of organizing projects I was part of. I wanted to be able to look further out to plan and strategize differently with people who are also interested in abolition but feeling like most of the movement spaces I was part of didn't have time for that because we're always scrambling to fill urgent needs.

So, when I think about [Making Room], I think about it as very directly wanting to feed into organizing practice. [Displaying] how eating and touching and holding seemingly believable artifacts from other worlds help us build toward those worlds through organizing strategies. I don't know yet precisely how that happens, but that's what I'm trying to figure out.

R: Can you say more about ‘Making Room for Abolition’?

note: ‘Making Room for Abolition’ was an installation by Lauren which was housed at Red Bull Arts Detroit in 2021

L: The space itself was kind of a backdrop; it wasn't the primary point of the installation. So for that reason, both the walls and the floor and all of the furniture was painted in a uniform color so it was all this dark, deep purple.

The exhibit was an installation of a living room from a world without police and prisons. It was something you could physically walk into and walk around. There were objects that I made that were mundane, boring things that might lay around your living room – books, newspapers, and graphic novels. But then also other physical things like mugs, vases, and clothing.

The objects were meant to tell a story. So if you were able to spend enough time with each of them, you could piece together bits and pieces of who lives in this house;

‘What do they do for a living?’

‘What activities are past times going on in this space?’

There were things that were relatable, but they were also intentionally signaling something very different about this world being that either there are no police or the police [presence is] shifting.

I should also explain that the room had three different timescales on it. When you first enter, you are in a space that was meant to reflect a present moment. In the second space, it was meant to be [about] 20 years off in the future; I think the year was 2047. Then in the farthest space, I didn't even set a timeframe because I wasn't entirely sure when it would be but it was really different.

There were maps that show the entire shoreline of Detroit being different. There were things that point to the ways we organize ourselves socially being different.

I was trying to demonstrate in the spatial design of that time variance that abolition is happening currently.

It's not just a point for us in the future that we can't imagine, and yet it's really hard for us to see that far in the future. The way that was reflected in the space itself was with the walls. So the room was a Venn diagram, meaning it was two shapes overlaid on each other. And because of that, it produced a third space in the middle.

So when you walked into the beginning of the room, you could see the furthest area the far future but you couldn't really make out everything that was there because the walls were made of this sheer fabric.

So there were things like that where the space had a purpose, but it wasn't the star of the show. It wasn't like the storytelling element.

[The installation] was sort of a container for multiple times space is a metaphor about how difficult it is for us presently to see this ultimate future. And then the objects in the room told stories about the future.

More on the intentionality of ‘Making Room for Abolition’

L: I think that abolition feels far off because the premise that we would just not have cops – even as we sit on this call, and we can hear the sirens in the background – It's just impossible for us to imagine. It's so big and so pervasive. It's such a part of our everyday lives that it feels like a complete, impossible impossibility to think about [cops] not being here.

I think that the point of making these fake things from alternate worlds or possible futures is that it helps us have more specific conversations and concrete conversations than if we just say ‘what happens if we banish the police?’

That isn't how it would work and when I say that abolition is happening today, I don't mean that police departments are gone. I mean that people are practicing the things that we need to fill the many gaps that would be left if we didn't have police.

The reason I decided to make a living room or to make a home space instead of something maybe more obviously associated with abolition like something related to a prison or whatever is because,

Number one: prisons have to go away – why would I imagine a future with [prisons] in it?

Number two: more importantly, I think that home is relatable.

Home is a space that we all can connect with, even if we don't all have one right now. The things in our homes, the things we collect, even the things we throw away, tell stories about our lives outside of home so they tell us about or [provides] evidence of how we work, how we eat, who we spend time with, what we value, what religions we practice, etc.

So because I believe, like many abolitionists writers, that we have to reimagine everything – not just police and prisons. I [thought] home feels like a good container for that because there's evidence of our food systems, our labor, our economy, our family, relationships, of our friendships, and so on.

R: How do you define abolition and why do you hold it close?

L: I think I define abolition as a political movement to and the carceral state and sort of punitive ways of dealing with harm and build alternative ways of intervening before harm happens, providing people with their basic needs so that they don't do the things that you might be driven to do out of desperation or lack.

I guess more broadly, building the systems that can support that on a society wide scale, but also as individuals in our families or in our schools or in whatever social spaces we participate in.

And why do I hold it close? I think I know I was talking to someone about co-ops the other day and they were like, not everyone has the time and energy to do co-op organizing.

The other component of this was that I said something to the effect of, if I just wanted to have a building with other artists, I can just do that. But I'm not interested in that. I'm interested in the political project of what it means to cooperatively own something

I don't think we can continue very long with many thriving with the systems that we have, and so it's imperative to me that I tried to build something. I think I feel the same way about evolution where we’re at this dead end; like we need something else, and I don't know precisely what that something else is.

But I know that it's just, it's gonna be extremely bad for a lot of people. If we keep going down this like carceral shitstorm.

R: Is there a need for art + organizing to intersect? Elaborate if so.

L: I do think it's important that there are forms of organizing that allow for creative expression.

And I think it's important that artists at least try to understand how their creative production can contribute to organizing or hinder it or shape it – I don't think all artists need to be organizers.

And in fact, I think there's some times that people do what they're good at and work together but maybe don't. Like maybe not an artist is doing organizing and vice versa.

I guess what I think is more important is artists understanding the political implications of their work, even if they're not making political art. For example, artists who do mural work: I think it's important that they understand the role they play and amplification of art washing and neighborhood flipping and all that. Or I think it's important that artists who work with galleries understand the implications of

where our money comes from. And who's funding the galleries? Who’s capable of buying our work? Because often, in order to make a living off your art, you have to price it in certain ways.

Some of that is in our control as artists and a lot of it's not so I'm not trying to say there's an outsized expectation on artists that they make these really intractable moral decisions that make it so they can't make a living off art. But I think it's important that we're aware and try. I don't know if that answers the question, but I think I think we should be informed. I think we should understand the power that artists hold and and the precarity that a lot of artists live in to do but I don't I don't necessarily think all artists should be like doing political stuff or I think because the reason I'm saying that is because I think everything is political anyway. So artists making choices about where we put our work or what mediums we work with or who pays us, those are also political decisions.

Even if the subject of your artwork isn't political on its own, I think it's important to understand that all the ways that we are political actors or the the ways that we have power or don't have power.

R: Who are your guiding ancestors in your practice?

L: I bring my grandmother into stuff a lot, but I actually don't know if she would be on board with this. I put her in the installation: I made my grandma's face the face of the grandmother in the family and wrote like an obituary about her, but it was [actually] about this fictional grandma.

I also made a memory jogger as part of the installation which is a West African tradition. It's also in the home that features the grandma in which I use my grandma's image. So for some reason I keep returning to my paternal grandmother.

I don't really know why; she was a sharecropper in South Georgia and I don't think she finished more than maybe middle school; raised a family. I guess maybe to some degree, I think of her as a guiding ancestor because of what she reflects for me beyond being my grandma like being a poor Black woman in the south, a sharecropper, and a descendant of slaves. These are categories that I think much of my work is trying to criticize or challenge or reimagine.

Maybe this is counterintuitive, but I think of my own parents – my dad is in the military. So I think it goes without saying to some degree he's bought into the system as it is and to carcerality not just here, but on an imperial global scale. I love him dearly and argue with him all the time about this because he's bought into the idea that the police just need reform or they need better behavior or whatever. And so I think there's a part of me that is often trying to figure out what it means isn't these kinds of things to a person who is that entrenched in the prevailing structure?

R: What about other artists who inspire you?

L: I'll say there's like abolitionist writers [I read]: Mariame Kaba, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, N.K. Jemisin, Octavia Butler

I also say that for this particular installation, which is not necessarily true of the entire body of work, but a lot of what I'm doing comes from a field called speculative design; or design fiction. There's a studio called Super Flex studio that did an exhibit a few years ago in London – I think where they've done it in multiple places – where it was a climate feature; whereas I did a living room. Their installation was an entire house. That was set in the climate’s future where people are eating bugs and growing stuff inside. And so it was a I think that premise of creating a setting where other people can enter and it's something that I drew heavily from there.

But if I'm being honest a lot of design fiction is very white and very technology focused and driven to the point that it doesn't always deal with like the social relationships and how they have to change in the features that are being imagined. And so I wanted to make sure I actually intentionally chose not to put any technological elements in the installation itself on purpose, because I didn't want to.

R: What are your hopes and dreams as you continue this work?

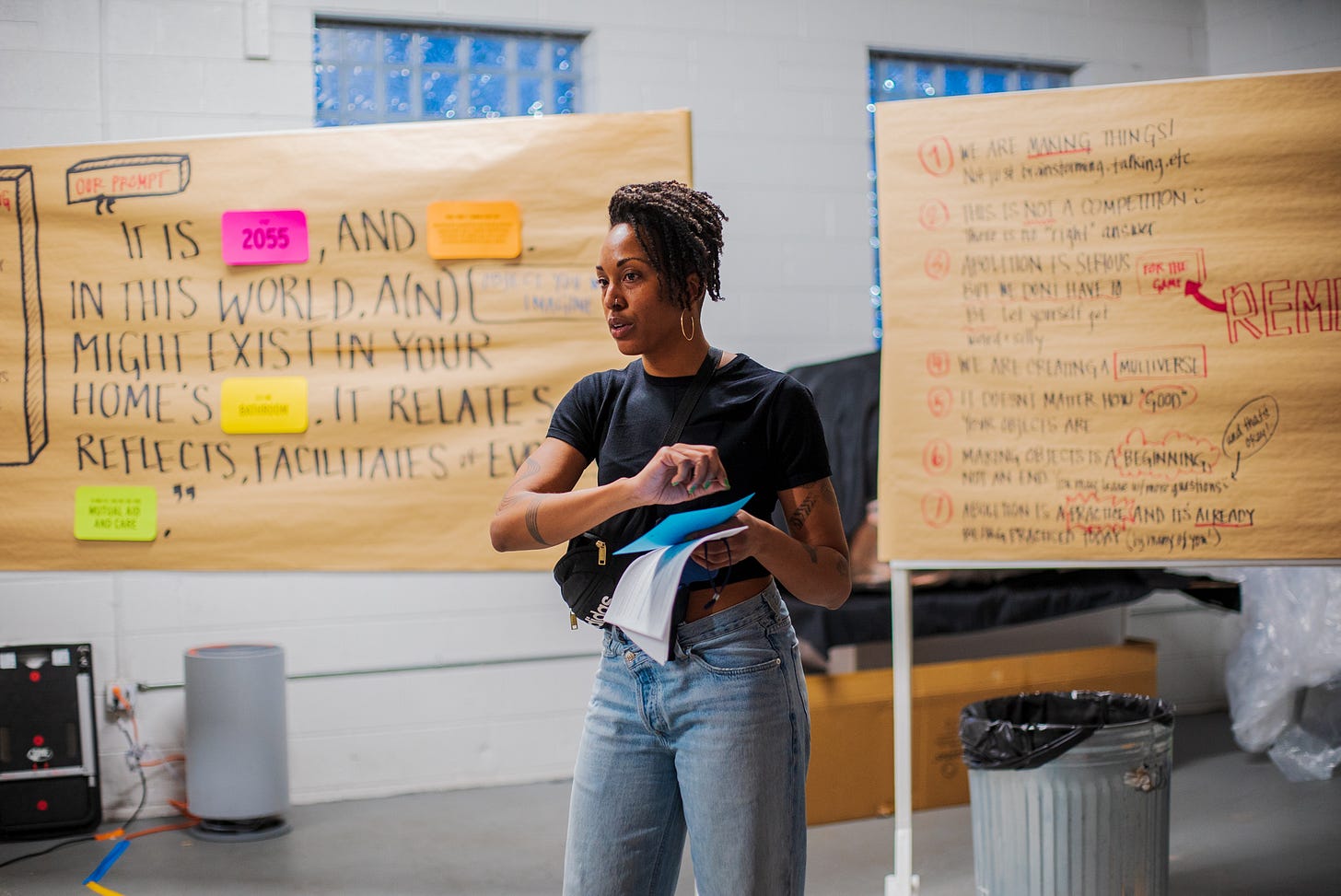

L: I'm looking for ways to continue inviting other people into imagining these worlds so there's not just my visions, or provocations being realized. And that's why I'm doing stuff like [facilitating] a storytelling accountability group and the workshops that I've been holding.

I'm very much trying to take it out of like my own personal creative practice and turn it into a collective practice.

And I don't have a perfect vehicle for that yet, but I'm like testing out these workshops to see what makes sense. So I'd say that I would love to talk to people who are also interested.